A Closer Look at Francisco Goya’s ‘Disasters of War’ (Los Desastres de la Guerra)

“Ya no hay tiempo” (There isn’t time now) (1810-1820), Francisco Goya

Haunting, macabre, and poignant, the series of 82 etchings by Spanish artist Francisco Goya known as “The Disasters of War” is a powerful reminder of the inhumane consequences of warfare.

The imagery Goya created for this 19th-century series is not pleasant, but this is by design. Instead of heroic depictions of battles, Goya sought to convey the tragic results of violent conflict through his harsh, realistic etchings.

This series went on to inspire other artists like Pablo Picasso and the novel “For Whom the Bell Tolls” by Ernest Hemingway. Despite its age, “The Disasters of War” remains one of the boldest anti-war statements ever made, reminding all of us that war can bring out the worst in humanity.

A War-Torn History

The year is 1808, and French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte has seized control of Spain. He installs his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as the country’s new ruler. However, the Spaniards refuse to accept the reign of the Bonapartes, and on May 2, 1808, the Spanish War of Independence begins.

This uprising became a part of the Peninsular War, which lasted from 1808 to 1814. The conflict was the bloodiest event in Spain’s modern history, with 215,000 to 375,000 Spanish military personnel and civilians dying during the war.

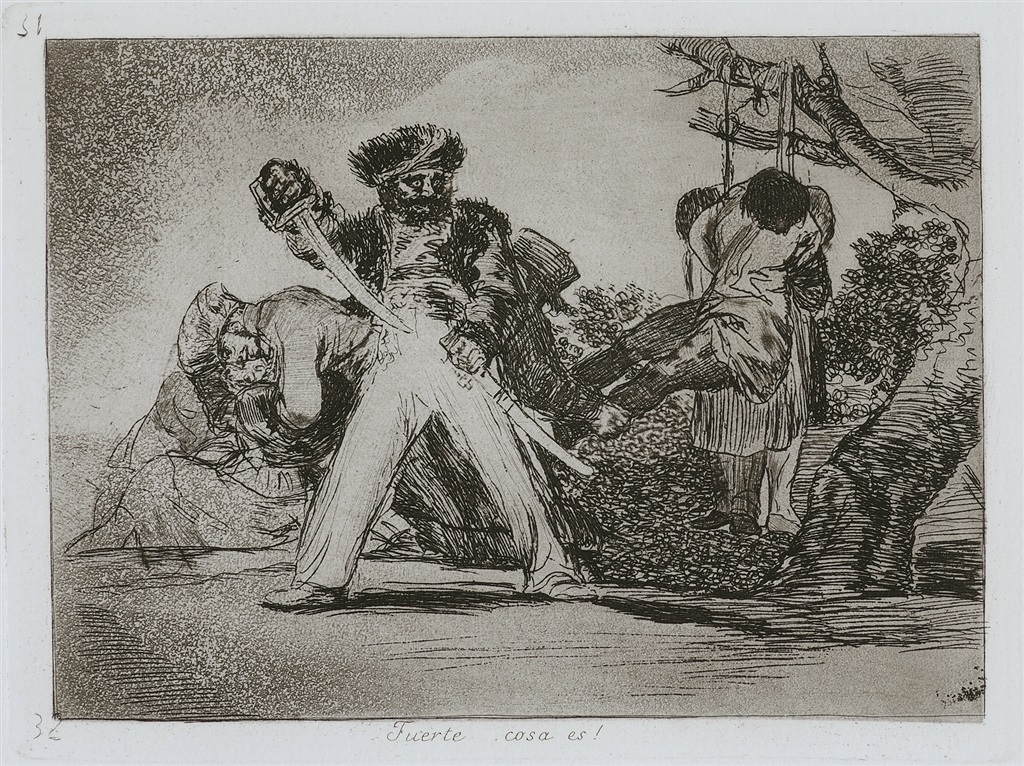

“Fuerte Cosa Es!” (1810-1820), Francisco Goya

Throughout the War of Independence, Goya retained his position as court painter to the Spanish Crown, though he remained neutral during the conflict. Once French forces were expelled from the country and Spain’s King Ferdinand VII was restored in 1814, Goya denied any involvement with the French.

However, Goya’s personal views of the war and its aftermath soon became readily apparent.

A Visual Protest

Goya began working on “The Disasters of War” in 1810. At the age of 62, Goya was suffering from poor health and deafness, but eventually completed a series of 85 etchings in 1820. Three small etchings called prisioneros (prisoners) are not included in the final “Disasters of War” series.

Despite the fact that Goya worked on many of the plates during the actual war, “The Disasters of War” wouldn’t be published until 1863, 35 years after Goya’s death. The series was finally printed by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, where Goya had served as director. The plates had been passed along from Goya’s son, Javier, to the academy.

“Por Una Navaja” (On Account of a Knife) (1906), Francisco Goya

Most historians suggest that Goya wanted to hold the publication of the series until the politically-charged images could be viewed uncensored, while others believe the delayed publication was due to the fear of retribution from Ferdinand VII’s regime.

A total of 1,000 sets of “Disasters of War” have been printed. The original 1863 edition had 500 impressions, with subsequent printings in 1892, 1903, 1906 and 1937.

“Que Valor!” (1810-1820), Francisco Goya

Aside from plate titles and captions, the only insight we gain from the artist comes from what he wrote on an album of proofs he gave to a friend (translated into English):

“Fatal consequences of the bloody war in Spain with Bonaparte, and other emphatic caprices”

Despite this lack of information, art historians agree “The Disasters of War” acts as Goya’s visual protest against the Spanish War for Independence and the subsequent Peninsular War.

The Disasters of War

For this series, Goya drifted away from traditional, painterly compositions to instead focus on narrative. He used realistic expressions, outfits, and settings to depict moments of torture, tragedy, and suffering. The 82 etchings are often categorized into three groups—war, famine, and political allegory.

“Con Razon o Sin Ella” (Rightly or Wrongly) (c. 1810-1820), Francisco Goya

The first 47 plates focus on the consequences of the bloody conflicts between the French and Spanish. Goya is unapologetic with his imagery, showing mutilated bodies, tortured captives, and violence against civilians by soldiers. Some of the titles indicate he witnessed the depicted atrocities firsthand—plate 44, for example, is called “I saw it.”

“Tampoco” (1810-1820), Francisco Goya

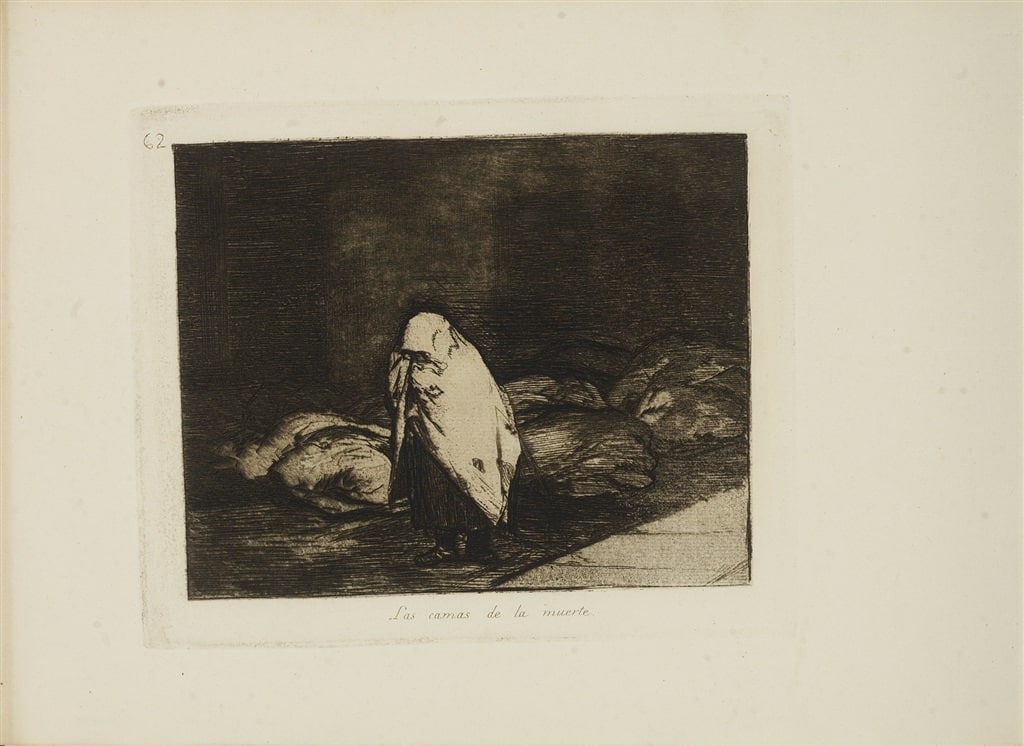

The next 18 (plates 48 to 64) portray the famine that plagued Spain following the end of French rule. The imagery focuses on the tragedies that occurred in Madrid, showing dead or nearly-dead bodies and people carrying corpses.

“No Se Puede Saver Por Que” (1810-1820), Francisco Goya

The final 17 show the demoralization of the Spanish citizens, having realized they fought to reinstate a monarchy that refuses to change. The plates express critiques of post-war politics as well as skepticism toward religious idolatry.

“Gatesca Pantomima” (Feline Pantomime) (c.1810-1820), Francisco Goya

When viewing the plates in order, it appears that Goya initially sympathized with his fellow Spaniards, but as the series progresses, it becomes harder to distinguish the Spanish victims from the French.

The Etching Process

Artwork from Francisco Goya’s “Disasters of War” on display at the Park West Museum

Instead of using color, Goya sought out bleak shadows and shade to express his stark views in “Disasters of War.” He did so through a combination of etching, drypoint, and aquatint.

Goya began his process by coating a copper plate with wax and etched lines into it with a sharp, needle-like tool. He then submerged the plate into an acid bath, causing the acid to bite at the exposed metal. The plate was then washed and the wax melted away.

“Asi Sucedio” (1810-1820), Francisco Goya

Goya next employed the drypoint technique. He scratched onto the plate directly to create more textured, uneven lines in his compositions. Lines created this way are softer when final impressions are made.

To create additional tonal effects, Goya used the aquatint technique. This involves dusting a plate with a powdered resin and heating it until the resin melts and hardens. Acid is applied to the plate and eats away at the metal around the resin. As a result, small channels are created that will hold ink depending on how long they were exposed to the acid—the longer the exposure, the darker the ink appears on the print.

“Las Camas de la Muerte” (1810-1820), Francisco Goya

The final step in the printmaking process was to ink a plate and wipe away the excess, resulting in ink remaining in the etched lines. The plate was placed on top of dampened paper and run through a printing press, transferring a mirror image of the plate onto the paper.

Through this tedious process, Goya exposed generations of art lovers to the sobering realities of war. Goya is often considered one of the first modern artists and, through his “Disasters of War,” we can understand why—his unflinching commentary on war and morality speaks to us through time, impacting us in the present in ways few artists can.

“Que Valor!” (What Courage!) (1810-1820), Francisco Goya

If you would like more information on “The Disasters of War” or collecting the art of Francisco Goya, contact our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 or sales@parkwestgallery.com. Register for our weekly live online auction today!