What Is a Serigraph? How Artists Have Embraced Serigraphy

Today, we’re talking a look at a medium that’s been around for over 100 years—serigraphy. It’s a medium that’s been used to amazing effect by artists like Andy Warhol, Igor Medvedev, Itzchak Tarkay, Peter Max, Romero Britto, LeRoy Neiman, and many others. But what exactly is a serigraph?

“Viridescent” (2007), Igor Medvedev

Certain terminology gets thrown around a lot in the art world. It’s important to not get lost in the jargon and really understand the difference between, let’s say, Expressionism and Impressionism or a lithograph and a caldograph.

Artist Igor Medvedev checking the colors on an in-progress serigraph in his studio.

The Origins of Serigraphy

Serigraphy is a fancy term for silkscreen printing, coming from “seri,” which is Latin for “silk,” and “graphos,” which is Ancient Greek for “writing.”

The word was coined early in the last century to distinguish the artistic use of the medium from its more common commercial purpose. Silkscreening is familiar to us in countless ways. It is used for everything from t-shirt logos to posters. The medium’s roots lie deep in ancient history, originating in China and Japan as a technique for applying stencils to fabrics and screens.

In that respect, silkscreening is allied to woodblock printing, which first arose in those countries for similar ends. Both techniques were adopted by European artists and artisans in the 15th century and were developed further for a wide variety of decorative and artistic applications.

“Fancy Evening” (2007), Itzchak Tarkay

Silkscreening, as we know it, however, dates only to the early years of the 20th century. In 1907, Samuel Simon of Manchester, England, was awarded the first-known patent for the process, which quickly gained wide use in commercial applications.

But it wasn’t until the mid-1930s that the medium’s artistic potential was recognized by a group of Works Progress Administration (WPA) artists in the United States. That is when true fine art serigraphy was born.

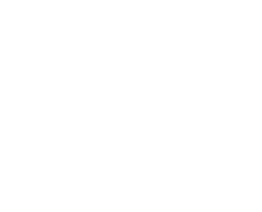

Serigraphy came into its own in the 1960s with the advent of Pop Art and Op Art. Artists such as Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Josef Albers, Peter Max, and Richard Anuzkiewicz saw the medium’s commercialism—which previously worked against its artistic acceptance—as a positive asset.

“Cherry” (2014), Peter Max

These painters, among others, exploited serigraphy’s technical potential and cultural associations, attributes that resonated with the spirit of the times.

How Serigraphs Are Made

Serigraphy has proven extremely popular, especially with younger artists, because the general process requires a minimum amount of equipment and materials, unlike most other forms of printmaking.

The medium is incredibly forgiving, easy to master, and adaptable. Serigraphy has an almost chameleon-like quality because it can utilize so many different related materials and techniques.

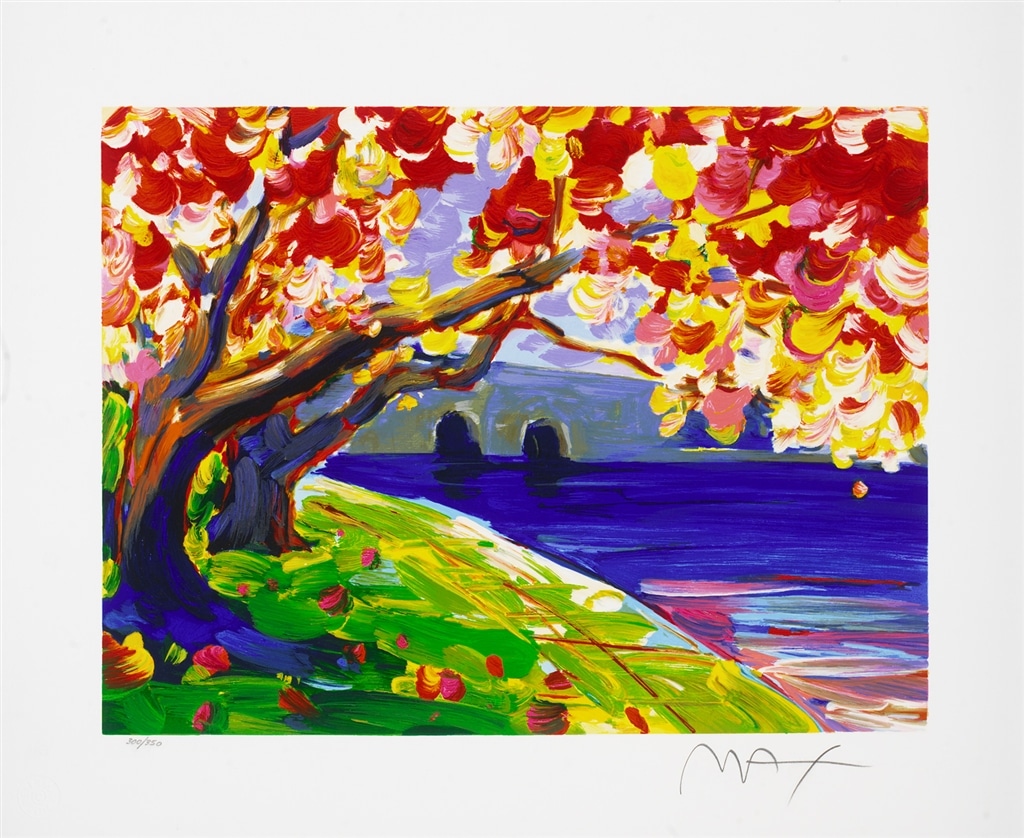

“Leaving the Paddock” (2008), LeRoy Neiman

At its most elementary level, serigraphy involves covering portions of silk or a similar material with a coating. First, the silk is stretched on a frame attached with hinges to a baseboard. Then, the window for the image is masked with tape, and a coating of shellac or glue is applied.

Any part of the silk left exposed becomes the design through which ink or other pigment such as paint is pressed using a squeegee or brush. This simplified description hardly does justice to the technical flexibility and artistic versatility of the medium.

“Restful Pause” (2007), Itzchak Tarkay

For example, the design can be transferred from an original study using photography, or lacquer film can be substituted for silk. Although most serigraphs are from negative stencils that are the reverse of the finished print in appearance, a positive stencil that looks just like the final product can be made from the same greasy inks (known as tusche) used in lithography.

In serigraphy, multiple colors are often involved, each color being applied separately to achieve a perfect image. The technical possibilities are almost limitless, as are the effects, which range from flat, simple colors to richly textured surfaces.

“Liberty Head II” (2015), Peter Max

Case Study: The Serigraphs of Igor Medvedev

Now that we have a better idea of what serigraphy is, let’s take a look at how one artist uniquely worked with the serigraph medium—namely, the late acclaimed Ukrainian artist Igor Medvedev.

Igor Medvedev and Park West Gallery Founder and CEO Albert Scaglione at Romi-Shaked Levan studio in Israel in 1999

Medvedev’s artwork is known around the world for its exceptional structure, emphasis on color, and masterful use of light and shadow. He worked in several different mediums throughout his lifetime, including lithography and serigraphy, before passing away in 2015.

Medvedev created his serigraphs in Rishon LeZion, Israel, at the Romi-Shaked Lavan studio, which is actually two small firms under one roof, owned by Ran Bolokan and his brothers. The studio craftsmen are themselves talented artists.

Usually, art serigraphs are made from photographs of paintings using a special reproductive camera to produce a few color separations. At Romi, the process is completely different.

“Scarlet Tide” (2006), Igor Medvedev

A 4×5 inch transparency of the painting is only the starting point. The Romi studio makes a screen for each hue—not just the primary colors, but every nuance.

In effect, the transparency is dissected into color planes much like geological layers. Each layer is hand-painted by a craftsman. There are literally dozens and dozens of screens, perhaps as many as a hundred or more.

Any or all screens (actually photographic film) may be divided into two or more color areas, so that a single image can have as many as 250 individual tints. The inks must be as transparent as possible, unlike those in three- or four-color lithographs and serigraphs.

Medvedev watches as artisans spread color over the silkscreen during the serigraphy process

The goal was to preserve the effect of the delicate glazes Medvedev used in his paintings. Not only did every screen have to be perfectly aligned, but the layers of color also had to work together to remain completely faithful to Medvedev’s original painting.

Thus, although the process makes use of technology, it is anything but mechanical. A great deal of trial and error experimentation requiring numerous proofs is required to achieve the intended effect.

“Golden Arrival” (2006), Igor Medvedev

Medvedev was heavily involved in the process. At each step, proofs were shipped to his studio in San Francisco. Using annotations and paint on mylar film, he meticulously corrected each proof sent to him until he was satisfied.

He signed his name only to perfect prints after the run was over. The rest were consigned to the scrap heap.

If you’re interested in collecting the art of Igor Medvedev or learning more about artists who masterfully use the serigraph medium, register for our weekly live online auction or contact our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 during business hours or at sales@parkwestgallery.com.