Illuminated Manuscripts and How They Were Created

First created in the sixth century and popularized across Europe into the 15th century, illuminated manuscripts centralized the command of Middle Age churches and monasteries, symbolizing a new era of textual literacy, spiritual devotion, and material culture.

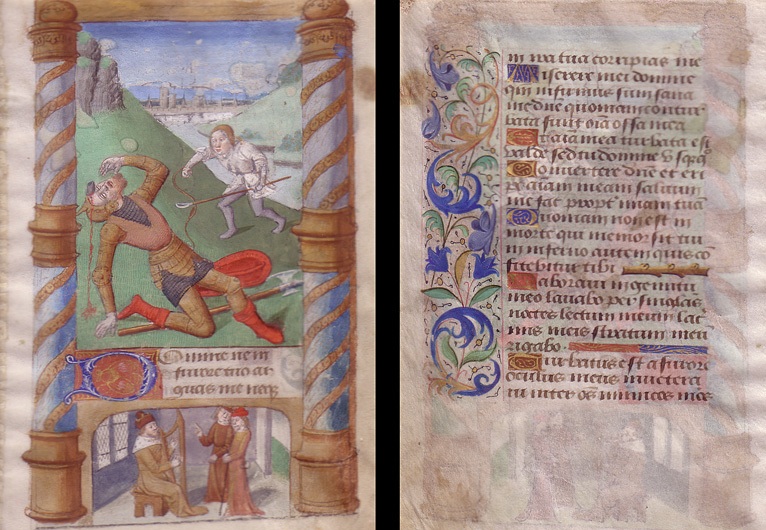

Illuminated Manuscript. “Christ Kneeling in Prayer in the Garden of Gethsemene” (c. 1475 France, Loire Valley).

Illuminated manuscripts were created using delicate, natural materials, such as gold leaf, silverpoint, vellum, and bright, mineral-derived paints. Each manuscript was carefully illustrated, gilded, and written by hand, requiring a high degree of craftsmanship.

Both the materials used to create manuscripts, as well as the war-torn state of medieval Europe presented an unlikely chance for these documents to remain intact and in good condition. Surviving illuminated manuscripts are treasured in museum and research institutions worldwide, as they present a rare window into the practices and customs of the Middle Ages.

“The Books of Kells” (c. 8th century). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Among the most well-known illuminated manuscripts is the Books of Kells (800 C.E.), considered to be Ireland’s national treasure and the pinnacle of calligraphy.

Liturgical and Ceremonial Use:

For the extent of their long history, illuminated manuscripts were used as visual tools for church services, or to support the daily devotions of monks, nuns, and laymen. Manuscripts created for liturgical use include the Missal, Breviary, and Antiphoner, while the Psalter and the Book of Hours were designed to inspire devotion into daily life.

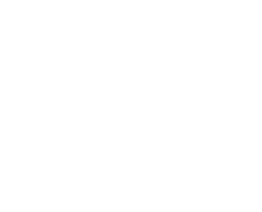

Illuminated manuscript. Psalter Leaf (c. 1501).

Oftentimes, churches and monasteries owned many large manuscripts to share among parishioners for daily prayer. Depending upon the size and function of each book, different prayers, verses, and illuminations were contained.

Illuminated Manuscript Materials and Production:

Until the 13th century, manuscripts were created solely under the devotion of monks and nuns across Europe. In exchange for arduous labor, monastic life offered the comfort of meditation, ascetic discipline, and eternal peace. In many instances, the monastery was the foremost intellectual, religious, and agricultural facility in a medieval city center. By extension, the ability to serve within a monastery was deemed a privilege.

The process of creating manuscripts required both physical and mental stamina, as the work was incredibly tedious, detailed, and demanding. Larger monasteries commonly housed scriptoriums, which were reclusive spaces built for the purpose of writing, copying, illuminating, and binding manuscripts. As a testament to their devotion, it was not uncommon for scribes and illuminators to work in solitude from morning until night.

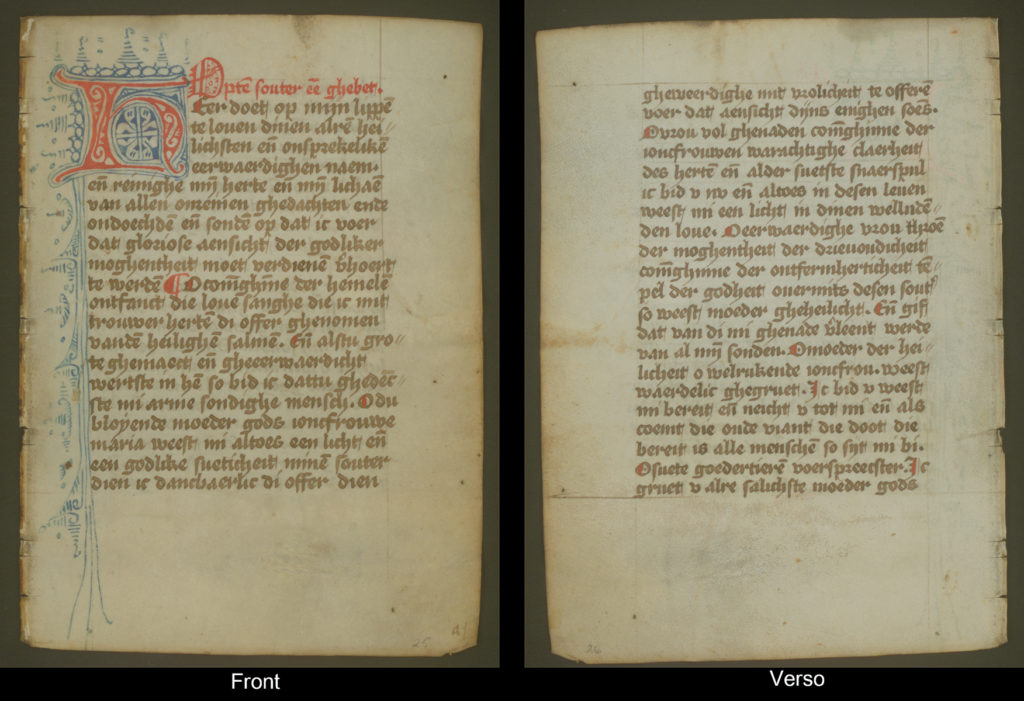

Illuminated manuscript. “The Crucifixion” (c. 1475). Leaf from a Book of Hours.

By the 14th century, the public demand of manuscripts rose alongside a growing, educated middle class. As a result, illuminated manuscripts began to be produced at large by commercial facilities in Paris, Rome, and Amsterdam, making them accessible to a wider audience. The shift of production—from monastery to urban workshop—was radical, yet instrumental in defining the standard of universal education.

While illuminated manuscripts were only available to members of the clergy in the early Middle Ages, manuscripts quickly became sought after by royals, aristocrats, and laymen. Families who commissioned these works often passed them on as heirlooms or displayed them in private libraries. In many surviving examples, family monograms, crests, and donor portraits are visible within the text.

By the end of the Middle Ages, illuminated manuscripts were created for secular use, resulting in an archive of decorated texts in mythology, poetry, and history. The arrival of the printing press in 1440 hailed the end of illuminated manuscripts. By the 16th-century, production plummeted to a record low, and once again, illuminated manuscripts were only reserved for the wealthy elite.

Types of Illuminated Manuscripts:

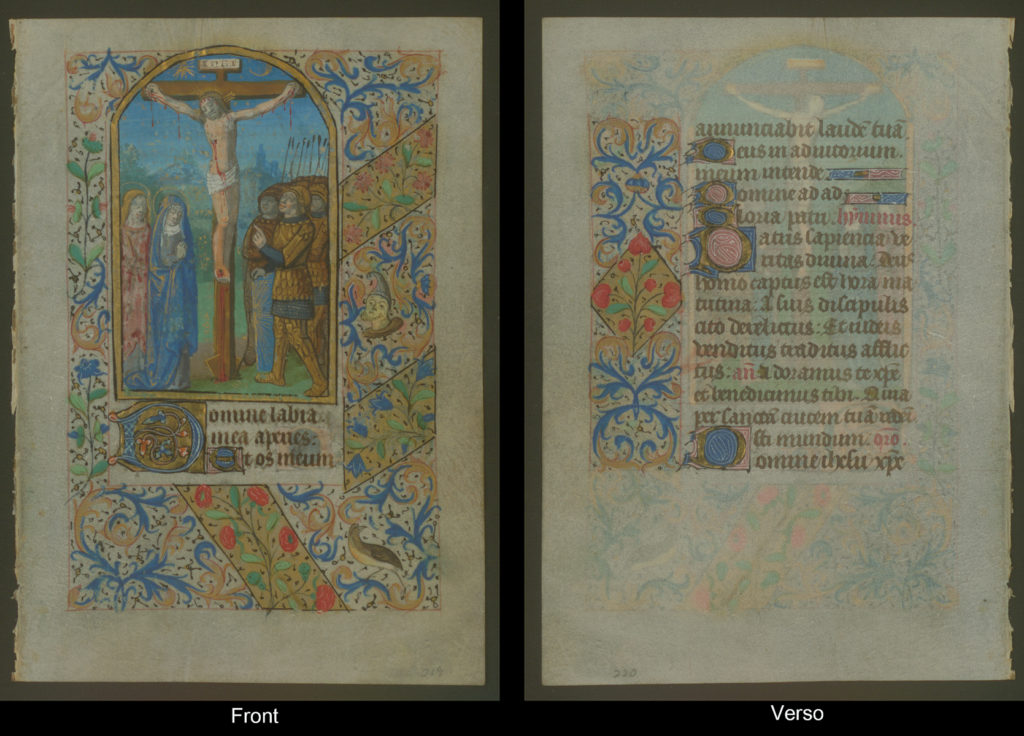

The Antiphoner: The Antiphoner was a volume of music used during daily religious services in the Middle Ages. All churches and monasteries were expected to own one, as it contained weekly cycles psalms, prayers, hymns, antiphons, and canonical readings. These manuscripts were usually oversized, as an entire choir would sing from one choirbook.

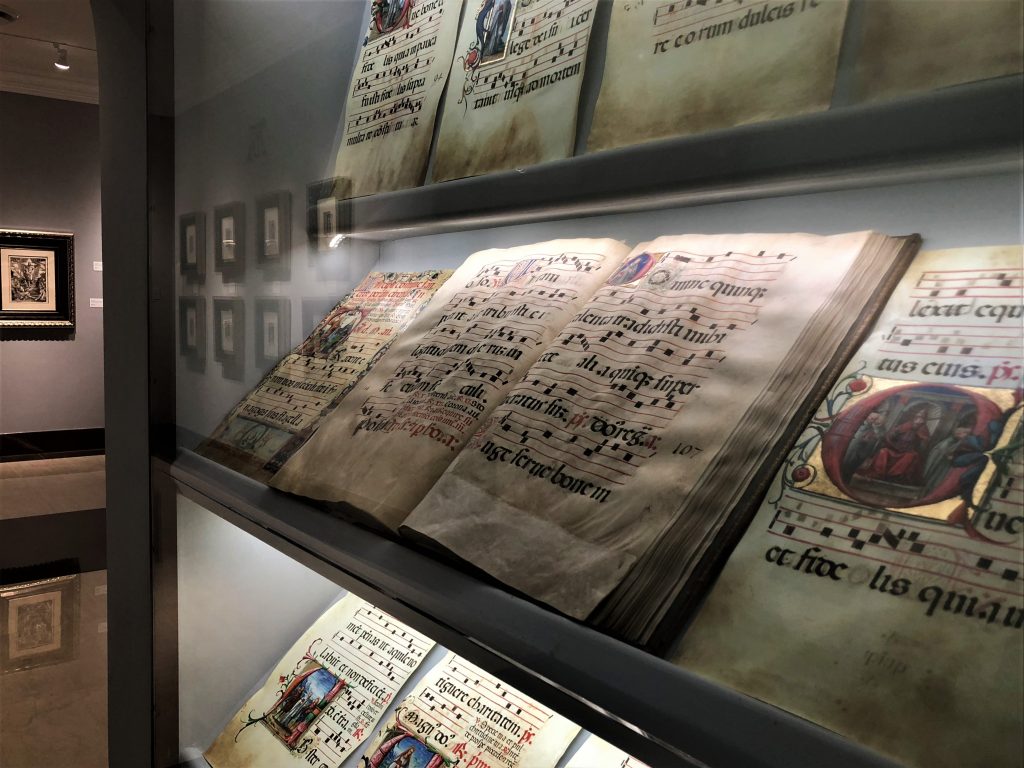

“Antiphoner containing Common of the Saints” (c. 1483 and 1500-1510). Currently on display at Park West Museum.

A rare antiphonal—dating back to the 13th and 14th centuries—is currently on display at Park West Museum. This antiphonal contains the entire Common of the Saints choirbook on 162 beautifully illustrated pages and is the only recorded volume of its kind to survive intact and complete.

“Antiphoner containing Common of the Saints” (c. 1483 and 1500-1510). Currently on display at Park West Museum.

The Book of Hours: The Book of Hours first evolved in the late 13th-century when interest in secular literary genres arose. The Book of Hours was a new type of devotional book that was designed for personal use, allowing lay people to incorporate ceremony into their daily lives. The book evolved from the monastic cycle of prayer, which divided the day into eight segments or “hours.” The Book of Hours also included a calendar of the church year, identifying major feast days and a list of venerated saints in colored inks.

The Psalter: The Psalter was one of the earliest versions of medieval manuscripts, first appearing as early as the 9th-century. The Psalter contained Psalms and other devotional texts which were recited during the week as morning and evening prayers.

The Missal: The Missal is a liturgical service book used by a priest to conduce Mass. A medieval missal was modular in fashion, and typically began with a calendar. The Missal contained the Canon of the Mass, the Sanctoral, a prescribed outline of saints’ days for the entire year; and the Common, a section of Masses in honor of saints not included by name. It concludes with special notes for votive Masses, which offer protection against temptation and bad omens, as well as the Mass for the Dead.

Illuminated manuscript. “David Slaying Goliath” (c.15th century, France).

The Breviary: The Breviary was not typically used at the altar, containing hymns, readings, Psalms, and anthems for morning and evening prayer. In its full version, the Breviary includes the whole book of Psalms. Unlike the Missal, which was used only by priests, Breviaries were also used monks and laymen. There are slight differences between monastic and secular Breviaries, most notably in the number of lessons contained in each. By examining the calendar within a monastic Breviary, scholars can determine whether it was used in an Augustinian, Dominican, Franciscan monastery.

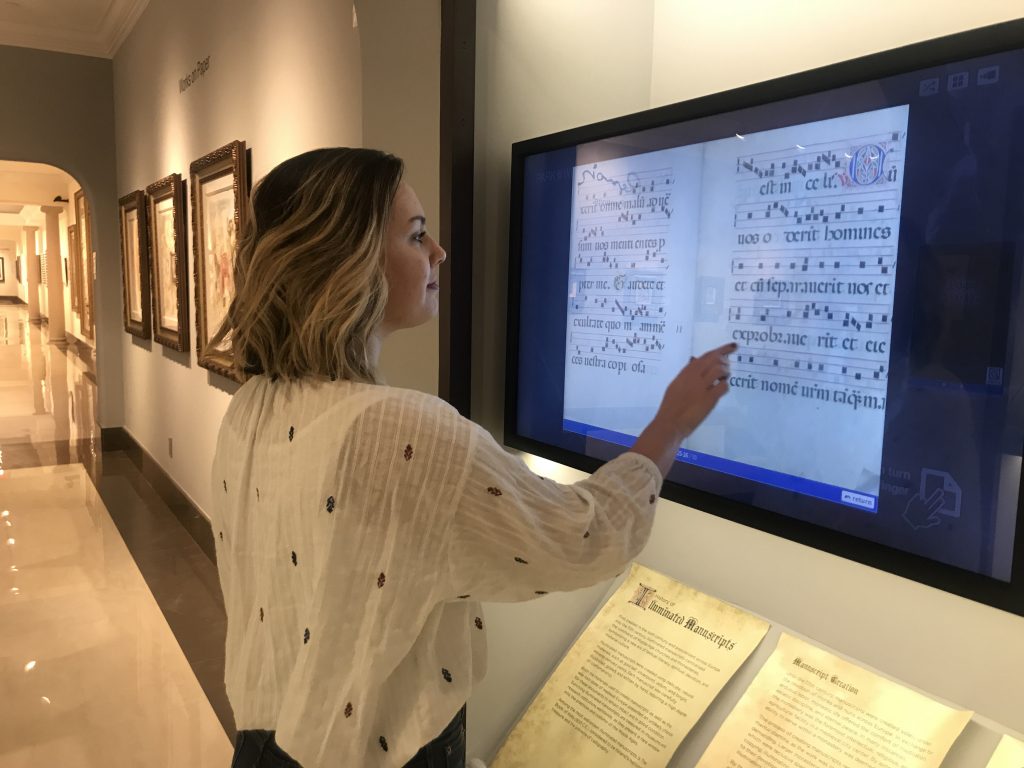

Guest interacting with the manuscript touchscreen at Park West Museum.

To collect a medieval illuminated manuscript from Park West Gallery, attend one of our exciting online auctions or contact our gallery consultants at (800) 521-9654 ext. 4 or sales@parkwestgallery.com.

Related Links: